Here. Our current ways are unsustainable. Change is essential. That’s the easy bit.

There. A different way of relational living and being. Circular economy, regeneration, low-impact, planet-friendly, carbon neutrality, balanced human ecosystems, Spaceship Earth. As concepts, also easy.

We know the reality is more difficult because we encounter political challenges and economic systems that impede change. This article is not about those. It is about time.

We are attracted to the image of the butterfly and its life-cycle from egg and caterpillar. In-between is the stage in which it cocoons itself and turns to mush while it transitions. Humanity does not have that option, or anything that resembles it. Daily life continues.

Over half the population lives in cities and that proportion is growing. Most science-fiction images assume that trend, with higher towers and greater density. Those cities have to be supplied with food and water. They need their waste removed. The food comes in on large trucks, often sourced from overseas by aeroplane. The waste leaves in garbage trucks or is pumped away for processing. Many of the inhabitants rely on pharmaceutical medicines. They own washing machines made with steel and copper, powered by electricity much of which is generated using gas. They may still use cars, but even public transportation systems use fuel. While these may increasingly have battery power, batteries are produced using constituent parts mined in remote places, transported possibly by air to processing plants and battery factories and then freighted again to other factories where they are assembled into cars, or phones, or whatever device you may have as part of your lifestyle.

These are massive systems, many of them global in their interdependencies and often dependent on huge corporations, the giants of fossil fuel, industry, aviation, container shipping and international mining. All of them the target of disapproval and demands that they change, sometime extending to hatred and even calls for their destruction.

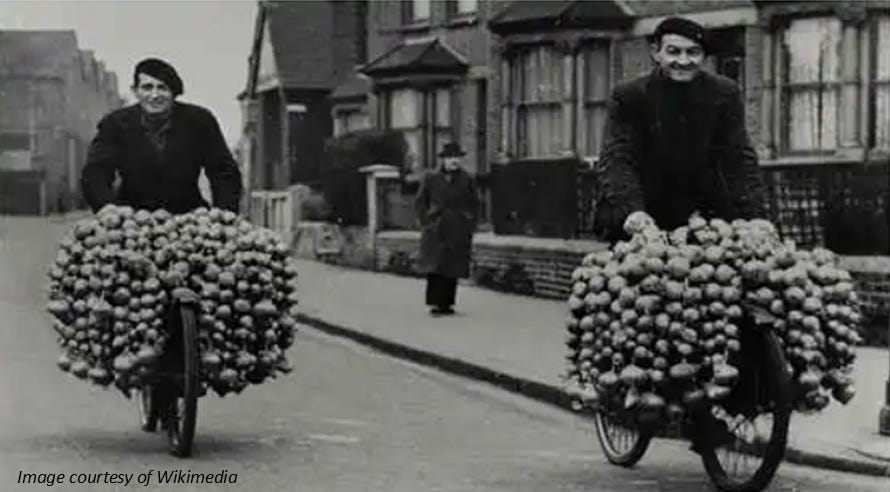

When I was little, sellers from France would arrive on bicycles to my English village and sell plaited strings of onions and garlic. It was all quite charming. The reality was that they had come in the back of lorries to places a few miles away. In earlier times, cities like London, much smaller then, had a massive problem with horse dung and stabling space. Their sewers were inadequate and the air smog-filled. Conditions for the poor were squalid. Anyone who imagines that there is some idyllic past that we can easily return to if the big systems were just destroyed, potentially condemns millions to disease and starvation.

In a recent workshop with a large oil company, I listened to a junior manager whose task as part of their energy transition agenda was to procure a tanker to transport hydrogen. You can’t buy one of those on Amazon Prime. The lead time from specification to delivery is four years. That is the physical aspect. Behind it is the commercial aspect, that the company must continue to exist while that happens and be able to fund the new development. If hydrogen is one of our future clean energy sources, potentially a better alternative to electric vehicles, we need such shifts to happen.

The familiar image of turning an ocean liner is often used to illustrate that large systems do not just “turn on a dime”. The butterfly illustration above warns us that we have to change how we live while continuing to stay alive. Politicians and industry leaders deserve criticism for past avoidance, current delay, for self-interest and much besides. At the same time, they reflect the twin realities that all humans are trying to maintain their lives and that both their survival and their way of life are dependent on large, complex and interdependent systems. The journey from here to there is a tightrope walk between near-instant collapse and longer-term non-viability in which destroying what we don’t want is not the same as creating what we do want.

There are personal choices in this too. I have just revealed that I have done some work with an oil company. Some people — including valued colleagues — choose not to do that. It is an ethical dilemma and I respect, even support their choice, but it is not mine. If I were a doctor, I would work with sick people. If I have any light to shine, it may be of greatest value where it is dark.

The transition will take time and we each must do what we believe will be effective, where we are.

What’s your choice?

I value that you go where no one is supposed to go. My share is in an entirely different part. I am working on an interpretation of the Christian faith that provides a spiritual narrative for the change and the time afterward to draw us forward again, as the early faith did from the warrior age to the traditional worldview.

I have never quite bought the story of the butterfly as a metaphor for societal or personal change for exactly the reason you are pointing to. There is no short period of halting life and proceeding differently, neither individually nor, especially, as a community. The example of the tanker is undercomplex because we have an idea, but not a full-fledged ideal we want to steer to next. We more or less see in part and stumble towards, hopefully upwards, toward that idea.

I am thankful for any fellow stumbler.