This is the first part of a recent paper in which I explore what fully embodied sensing is and then deliver some scientific understanding of how it is even possible. What is the nature of a reality that would enable such a capability to exist? Recognising that reality, how would we develop and make use of this capacity?

Read Part 2 here.

What is Embodied Sensing?

It is always best to begin with a shared understanding of what a key word or term means, and more so than usual when the concept is poorly understood. I will begin with two definitions:

1. The power or faculty of attaining direct knowledge or cognition without evident rational thought and inference; and

2. Spiritual insight or immediate spiritual communication.

In this paper I focus primarily on number 1. However, it will become evident that the analysis crosses boundaries into the realms to which a word such as “spiritual” may be applied. If there is some discomfort that such a word is showing up in a paper with “science” in its title, I invite you to bear with the analysis.

A Sceptical Beginning

The current scientific paradigm is so strong that scepticism pervades the territory of this analysis, most particularly because its methodology is oriented exclusively towards what can be proved objectively, and wherever possible, what can be detected by apparatus. Embodied sensing or intuition, on the other hand, appears to be a subjective experience.

However, the boundaries are not that clear. Much of science depends on observation of limited data, in which we attempt to discern patterns and from them make extrapolations into theory. We could not discuss evolution or ethology otherwise and the entire discipline of psychology straddles the boundary, attempting to make sense of subjective experience with MRI scans.

What is the origin of this paper? In order to explain why I am engaging with this topic and also to provide some more concrete, less conceptual indication of the territory, I will introduce my own experience into this narrative. I do not offer this as evidence but as background sense-making.

I was raised as an atheist and trained as a scientist. I had no interest in spirituality and if I had thought about embodies sensing at all, I would have described myself as having none. Then I found myself on a training course for (I thought) stress reduction and creative thinking. It emerged that it was more than that and I went along with it in an open-minded and curious way.

Personal Experience

On the last afternoon, we each went through exercises using the techniques we had been taught. In these exercises we would be given the name, age and approximate location of an individual, known to one other of the participants who had written down some basic facts about that individual. This information was in the hands of a third person so that no “prompting” was possible.

My experience during the exercise was of “tuning in” to the subject individual (David, a 27-year-old male living in Devon) using the techniques we had practiced. For a long time I was getting nothing, until I tried a particular approach in which, rather than trying to “see” the person or “hear” information about them in my mind, I visualised what it would be like to be that individual. The effect was instantaneous. I had the strong sense of there being pain in the rear left side of my head and I spontaneously grimaced and twisted my neck. Without any real thought, I asked the observer if the person had pain from some condition like a brain tumour and was told that this was exactly what was written down. I used other techniques to attempt to send healing (this being another purpose of the training) before bringing my attention back and participating in the experiences of other students.

Of the twenty or so people in the room, all but two had some kind of success in this kind of detection — enough that they knew with confidence that they had detected something that they could not have known by any “normal” means. I therefore had to acknowledge not just my own experience but that of several others, none of whom had given any indication of previous development or gifts in such areas.

For a while, this experience was merely a curiosity; later it began to bother me a lot. All my scientific training told me:

that there was no known mechanism by which such things can happen;

there was no physical medium by which such information is known to pass;

there was no way known to science in which the information itself is “published” and available;

there was no way to understand in any scientific terms how I could have “located” the correct individual based on just a name, age and location; feeling directly what someone else was experiencing was simply not in the frame, not catered for.

My unavoidable conclusion: the science I had been taught had to have been flawed in some way. I subsequently observed other courses in which larger numbers of people went through a similar experience. Then, having trained as a teacher for the method and seen those whom I taught having similar success, I added two more features to the list above: every normal individual has the potential for similar capability; and this is a trainable skill.

All seven of these points are significant. Each of them individually challenges the scientific status quo. My mind could not let this go, and I spent many years exploring the territory in order to construct a science that would remain consistent with all that was already known, but also encompass the reality in which all of the above could happen. This paper presents the key features of that new scientific viewpoint, and a small sample of the data that support it as published in my 2013 book The Science of Possibility.1 In order to do this, we join the dots to link the following elements:

The physics of energy and matter; what governs the shapes that energy can take?

The part played by information, connectedness and time.

What does it mean to speak of a field of information?

How do our bodies and minds engage with the realm of information? The cellular coordination that provides the levels of sensitivity and coherence for sense-making and consciousness.

How do the activities of our minds carry out that sense-making and how can that affect our bodies?

How does the connectivity between us and our external world show up? Some evidential challenges to our conventional perceptions of ourselves and nature.

Presenting an alternative narrative for creation based on a scientific model of autopoiesis (self-creation), which makes sense of the evidence and meshes conventional material reality with the non-ordinary realm of connected consciousness and spiritual experience.

Acknowledging the nature of human experience as a reality-creating process.

Discussing the realm of the “nondual” and the boundary across which our embodied sensing or intuition operates.

The potential implications for individual identity and the stories we make of our existence.

Application: Presenting many of the ways in which embodied sensing and connection are used, leading to the potential choices for development.

That is our route-map, so let us begin the journey.

The Nature of Reality

What does it take for embodied sensing to be possible? Our earlier definition refers to direct knowledge; so, what is it that we know? The simplest answer is information, facts or data about the world we inhabit.

If asked what the world is made of, a typical answer would be given in terms of physics and would say matter and energy. Since the days of Einstein’s E=MC2 equation, we have known that energy comes first. Matter is something that energy can be formed into. The story of the “Big Bang” describes our universe as having begun from an inconceivably large quantity of energy compressed into an incomprehensibly small amount of space. In that sense the New-Age expression “Everything is Energy” can seem to be an accurate description of the cosmos.

However accurate it may be, it explains nothing and fails to satisfy as an answer to the most fundamental of all scientific questions, such as “what are we?” and “where do we come from?”. We can also see that even when energy is shaped into the other basic component, which is matter, there is still nothing for intuitive sensing to engage with. There is no information.

Energy and matter fit into the model of objective science because both are measurable. In that model, it is the process of measurement which supplies us with information. As a result, it appears that information is not something that is part of the universe itself. Instead, it seems to be part of the human world, so that in the absence of humans to ask questions, information would not exist. There are many more complicated versions of this question, as with Plato’s enquiry about the falling tree in the forest. “If there is no-one there to hear it, does it make a sound?” he asked, drawing Bishop Berkeley’s response that “God” would hear it. In this analysis I am strongly inclined to avoid millennia of epistemological debate. Even so, the problem remains; what is information?

The challenge deepened with Werner Heisenberg, who, when examining the relationship between energy and matter, concluded that we could never be certain. If we look at the energy (a wave), we can determine how fast it is moving. If we look at matter (a particle), we can locate it. But it is impossible for us to know both. Worse than that, the act of measuring changes that which is measured. The choice of which measurement to make determines whether we are observing a wave or a particle. This is not just a theory. In attempting to unravel this paradox with a key experiment known as the double-slit, physicists came up with an even more uncertain result. It demonstrated that light and matter can simultaneously display characteristics of both classically defined waves and particles. It is proven that what is taking place is not certain, but probabilistic. It is in a state of quantum uncertainty or flux.

If this makes it seem that the information is indeed only in the human realm rather than in the universe itself, this is also untrue, and once again that is experimentally provable. Initially a thought-experiment by three physicists, Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen, the EPR paradox questioned what would happen if a pair of particles, whose states were known to be a complementary pair (for ease think of them as left-handed and right-handed) but where it was unknown which was which, became separated over a large distance. What would happen if we measured just one of them?

The result, as determined in an experiment by Nicolas Gisin, turns out to be that the instant one particle’s status is determined (e.g., right-handed), the left-handed status is known to the other. This takes place regardless of the distance between them, a phenomenon known as “entanglement”. It is as if the information has travelled faster than the speed of light, but is more likely an indication that the information, rather than travelling, is simply present everywhere. The answer to Plato’s question is that when the tree falls, the forest hears it.

One indication that information is everywhere comes from data on precognition. An illustration of this was given in the 1927 book by physicist and aeronautical engineer J.W. Dunne. He had repeated instances of dreams in which he experienced something that happened later. One vivid example was a dream about the Burntisland train derailment of the “Flying Scotsman” mail train. He reported the dream in the autumn of 1913, of specifically and vividly seeing the location, and described a repeated image of the train and carriages at the bottom of the embankment. He gathered that this event was to occur at some time in the following spring and it subsequently took place on April 14th. More than half of Dunne’s book contains a full investigation of the physics, presented in the context of Einstein’s relativity theory that was relatively new at the time. He subsequently conducts a brief experimental investigation to determine whether others can produce similar experiences. He is rigorous in his criteria and the number of subjects, seven including himself, is small. Nevertheless, out of 88 recorded dreams, he classifies five correlations with the future as “good” and another six as “moderate”. One of the subjects (not himself) he describes as a startling success, with three good correlations. Even five correlations are a potentially significant result, when zero might be expected.

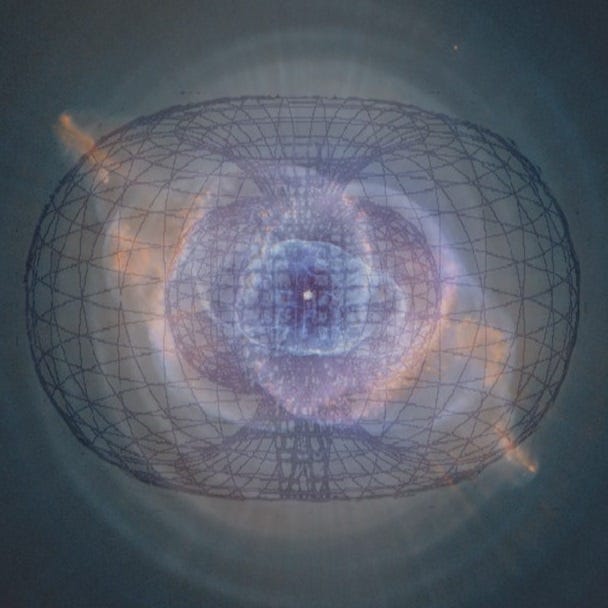

The Field

The notion that information is present everywhere, and independent of time or space, leads to the concept of information being a “field”. There are numerous expressions of such a concept in the literature on consciousness, including Dr Ervin Laszlo’s “Akashic Field”,2 Gregg Braden’s “Zero-Point field” and Lynne McTaggart’s simple “the Field”, and all of these have resonance to more ancient expressions, many of them from oriental religions.

The notion of such a field in relation to consciousness is regularly challenged by sceptics for being vague. But it is in the nature of a field that you cannot pinpoint the thing itself, only its effects. If you think of your school science demonstration where you watched iron filings reorganise themselves around a magnet, the field itself remains invisible. You cannot see it around the magnet. You can only see its effects on filings. By extension, all of electromagnetism is founded on the measurement of its effects on other things.

A field of consciousness is not different in principle. The evidence challenge it creates is that human beings are the detectors. There are some experimental results with the use of certain specific crystals (metaphorically slightly reminiscent of the earliest cat’s-whisker radio receivers), but so far these have not been validated other than by reference to human experience. More independent systematic results may not be available for years.

As in many areas of science, we rely in the meantime on accumulating volumes of sample data using multiple subjects in order to produce statistically reliable numbers. Subjectivity is reduced or eliminated by creating viable patterns of aggregate data. Much of biology and medicine begins this way, because intervening in order to measure living systems carries greater risk of damage and may also disrupt the data.

Note that there is a probable difference between the electromagnetic field and the one that governs embodied sensing. While some information may be electromagnetic in character, it is difficult to frame either my embodied sense story or a precognitive dream solely in terms of electromagnetic frequency. Many such sensed or intuitive experiences involve whole pictures, or movie-like sequences, or verbal narratives. The field, whatever it may be, appears content rich. What does that take? What is in the field and what is in our experience of it?

The Biology of Sensing

The narrative so far engages with questions of what is it that we are having knowledge of, and how is information carried. Our eyes see what is in their range of vision and sound has to be very loud (like an aeroplane engine) to carry any distance. In contrast, with embodied sensing we are encountering information that is accessed over long distances even while being very subtle. What is it about our biological make-up that makes this possible?

The answer is more complex than might be expected. You might assume that it is something that is happening in the brain, but this would be a mistake. Similarly, while we are accustomed to think of our eyes as seeing, ears as hearing, and so on, this sensing is a whole-body event. This is not to say that the brain is not important; in the end, everything that we experience is interpreted and delivered to our awareness through that apparatus. However, the experience as a whole involves coherence, connection, communication and sensitivity across our entire system. There are many pieces to the puzzle, so we will look at some of them in detail and then examine what is involved in assembling them to form a picture.

A good place to begin is with the heart. Conventional science looks on the heart as a pump, its sole function being to get blood around the body. In reality, the heart itself has 40,000 neurons and there is a direct neural pathway from it to the brain, sending more information than it receives. The heart pulse is present in the foetus before the brain is formed and it creates a wave through the body, synchronising electrical activity.

The heart is the strongest source you have of bio-electricity, creating a field that extends 3 meters around the body. It produces hormones, chemical messengers such as dopamine and noradrenaline, and it regulates oxytocin levels. In positive emotional states, the field around the heart becomes coherent; the reverse happens under negative emotions. In his TED talk,3 neurophysiologist Alan Watkins demonstrates in a matter of minutes how simply by regulating our breathing, we can generate that coherence so that it shows up in the smoothness of our pulse and he describes how this can be a key to improved performance of both physical and mental tasks. In this he confirms what people knew long before such scientific measurement, and what yogis taught for millennia. Regulating our breathing is one key to our internal connectedness.

It is normal for you to think of yourself as a singular entity. Here I am in my biological wholeness. Even if you know that you are made up of forty trillion cells, you do not give that much consideration, nor do you pay any attention to your spleen, your lymph glands or your liver (unless you have recently drunk too much alcohol). The underlying reality is that all of these components are co-ordinated and regulated together. You run and your heart and lungs speed up. You spend time in hot conditions and you sweat to keep your temperature within a safe range.

There are many mechanisms that support that cellular co-ordination. Here are a few of them:

Your body has many chemical messengers that circulate throughout it. When our adrenal glands produce adrenaline, that hormone delivers messages to millions of cells that have to be activated in your fight-or-flight response. It is one of over fifty such messengers that regulate activity, sometimes short-term like that example and others long-term, like reproductive cycles.4

In her article “The Tao of Biology”,5 Dr Mae-Wan Ho described macromolecules which “… associated with lots of water, are in a dynamic liquid crystalline state, where all the molecules are macroscopically aligned to form a continuum that links up through the whole body, permeating through the connective tissues, the extracellular matrix, and into the interior of every single cell. And all the molecules, including the water, are moving coherently together as a whole. The liquid crystalline continuum enables every single molecule to communicate with every other. The water, constituting some 70 percent by weight of the organism, is also the most important for forming the liquid crystalline matrix, for intercommunication and for the macromolecules to function at all.” (My emphasis in bold.)

Bruce Lipton, in his book The Biology of Belief,6 describes the complexity of a physiological system in which each individual cell has many processes, both interior and interactive with their environment. “Each eukaryote (nucleus-containing cell) possesses the functional equivalent of our nervous system, digestive system, respiratory system, excretory system, endocrine system, muscle and skeletal systems, circulatory system, integument (skin), reproductive system and even a primitive immune system, which utilises a family of antibody-like ‘ubiquitin’ proteins”. He then describes the connectivity through the system, showing how the activity at cell boundaries functions similarly to junctions (logic gates) in transistors. The result is that in-between cells and their environment are membranes, connecting cells like microprocessors.

Fritz-Albert Popp,7 following an accidental observation that plants could communicate with each other when their roots were contained in glass, but not in silicone pots, investigated the nature of photonic (light) communication in biological systems, including humans.8 The results gathered over 25 years by him and others indicate that there are phase-locked loops and oscillations in coherence that resemble the laser-light characteristic that removes scattering. In multiple arenas he and others showed that light is a co-ordinating function both within the organism and between organisms. These emissions are detectable using photomultipliers and led Popp to say, “We know today that man, essentially, is a being of light.”

Looking closely at the microtubules that surround neurons, Professors Stuart Hameroff and 2020 Nobel Prize winner Roger Penrose observed their crystal-like lattice structure, hollow core and organisational capacity. Their size appears well-fitted to the transmission of photons in the UV range. As described, “Theoretical models suggest how conformational states of tubulins within microtubule lattices can interact with neighbouring tubulins to represent, propagate and process information as in molecular-level ‘cellular automata’ computing systems”.9 This led them to propose the “Orch OR” model for consciousness.10

The above paragraphs are extremely abbreviated summaries of extensive and complex bodies of work. There are many more. The intention here is not that you should understand them, and certainly not in any detail. The point being illustrated is that there are several different mechanisms by which our bodies are capable of detecting very small interactions with our surroundings, and that there are ways to create coherence across these systems so that even extremely small shifts in the Field can produce enough of a signal for us to recognise their combined informational content.

This is an emerging area of scholarship and very little yet is academically robust or formed into a higher-level picture, but it is no longer “wacky” or weird. The terrain that is now referred to as “quantum biology” arguably began over ninety years ago with a lecture from Niels Bohr. It has been gaining traction in the last few decades, supported perhaps by the availability of very fine low-energy research tools, as indicated by the establishment of a doctoral research centre at the University of Surrey, led by Professors Johnjoe McFadden and Jim Al-Khalili, a regular BBC documentary creator.11 Here are a couple of illustrative quotes from Al-Khalili about living open quantum systems:

“You are no longer solving the Schroedinger equation because your quantum system of interest is surrounded by an environment that is playing a very important role.” Note the clear resonance of this statement to Bruce Lipton and epigenetics referred to below. And in answer to the challenge regarding how it is even possible for such delicate and ephemeral effects to have a functional role in biology: “There are hints that life has evolved the ability to maintain these quantum effects for biologically significant periods of time”.12

The theme of relationship between the very small and ephemeral and higher levels of coherence/observability is as relevant to the realm of information itself as it is to the underlying biology. There is significant potential for direct connection between the two.

What Happens Internally?

“When Timmy drinks orange juice he has no problem. But Timmy is just one of close to a dozen personalities who alternate control over a patient with multiple personality disorder. And if those other personalities drink orange juice, the result is a case of hives.

The hives will occur even if Timmy drinks orange juice and another personality appears while the juice is still being digested. What’s more, if Timmy comes back while the allergic reaction is present, the itching of the hives will cease immediately, and the water-filled blisters will begin to subside.” 13

Our bodies are more complex than we are yet able to know. The relationship between information, thought, emotion and physical response is something we have not yet fathomed. The story quoted in the article comes from psychiatrist Daniel Goleman, who has since become very well-known for opening up the field of emotional intelligence.

In re-telling this story in his 1989 book Quantum Healing: Exploring the Frontiers of Mind/Body Medicine, Dr Deepak Chopra points out (p. 117) how it shows that consciousness cannot be located. Timmy’s response indicates that the “intelligence” is in the cell, and Chopra goes on to say “[The cell’s] intelligence is wrapped up in every molecule, not just doled out to a special one like DNA, for the antibody and the orange juice meet end-to-end with very ordinary atoms of Carbon, Hydrogen and Oxygen. To say that molecules make decisions defies current physical science — it is as if salt sometimes feels like being salty and sometimes not.”

This also connects to the core message of Bruce Lipton’s Biology of Belief. His title refers to the understanding that what conventional science has presented as responses driven by the genes, frequently are not. In what has since become known as the study of epigenetics, it is increasingly apparent that our development and our biological responses are influenced by a sophisticated interplay between the blueprint (DNA) and the environment. The blueprint metaphor is relevant. The precise character of a timber-framed house would be different depending on the use of different species of pine, or even oak.

Our internal information processing is taking place in many different layers, from emotions to beliefs to unconscious responses (like allergies) to fully conscious choices and discriminations. We are not passive, but actively interacting, sometimes intentionally and often without any cognitive awareness of what we are doing.

So, before moving on let us remind ourselves that the puzzle we are assembling is constructed from pieces that illustrate the ways in which communication could be happening beyond the realm of our conventional senses. At this point we are continuing the parts of that picture that are relevant to living systems and to biological function. The keys continue to lie in the areas of communication, coherence, sensitivity and detection.

What Happens Externally?

This is a rich area, and so crammed with stories that the anecdotal material could be almost endless. Bearing in mind that we are trying to bridge the gap between subjective experience and data which is in some degree measurable or externally validated, the examples that follow will emphasise those aspects. Even so, before doing so, it is appropriate to talk briefly about the very wide geographical commonality and long-term consistency that is present in such stories.

Our modern viewpoints struggle to understand the way in which traditional and indigenous cultures function. We have centuries of reporting, starting with early explorers and developing into more embedded studies by professional anthropologists adopting formal academic distancing. In more recent years, travellers like Bruce Parry14 have engaged with tribes they are visiting and participated directly in their ceremonies. A few westerners such as Eliot Cowan15 and Alberto Villoldo16 have spent the years necessary to become acknowledged by their indigenous teachers as “qualified” shamans. Carlos Castaneda17 similarly wrote an extensive series of books in which he did his best to communicate to the Western mind, the nature of reality as seen by the mystic “Don Juan” through the non-ordinary, peyote-induced consciousness. Michael Harner,18 an investigator based in Britain, continues to do direct research from within our Western context. Conversely, Malidoma Somé,19 a West African with three master’s degrees and a PhD from the Sorbonne, documents his own initiation into the shamanic culture of the Dagara.

All of these examples might be mere anecdotes, were it not for the deep continuity that runs through them. They are not a faulty side-effect of the way human brains are constructed. Michael Harner quotes historian of religion Mircea Eliade’s conclusion20 that shamanism underlies all other spiritual traditions on the planet. Some such cultures use drugs to achieve altered states of consciousness, which easily attracts dismissal or suspicion from scientists who desire an easy excuse to treat their experiences as psychotic. Many cultures do not use drugs, though. Some induce altered states through ritual and chanting. However, these are not essential either, and the engagement with other fields of information sits very close to the realm of embodied sensing we are investigating; others such as Findhorn founder Dorothy Maclean21 and Perelandra garden creator Machaelle Small Wright22 who have engaged in direct relationship with nature do so through a more meditative approach. A full reading of such examples compels the conclusion that there is worldwide commonality across cultures and no discernible boundary between shamanism and embodied sensing. They are different applications of the same technology.

There are many who dismiss “animism”, the idea that other parts of the living world have some kind of “spirit” that we can communicate with, as “magical thinking” — a term which places the experience in the same context as a child’s belief in the tooth fairy, or their imaginary friend. The descriptions that follow should be regarded as strong indications that the shamanistic reality is far from being some kind of childish fantasy practiced by “primitives”. What all these people across the globe have been experiencing is built into the universe.

Let’s look at one investigation of communication in the world of living systems and a few illustrative descriptions.

The story begins in 1966, concerns America’s foremost lie detector examiner, Cleve Backster, and stars a houseplant called Dracaena massangeana.

You may know that a lie detector works by measuring how much electricity the skin will conduct. Backster decided on impulse to attach this device to his potted Dracaena and see how it responded to being watered. You might expect as Backster did that more water means more current will pass. However, the trace on the paper showed a fluctuation that was in the opposite direction — downwards, with a kind of saw-tooth motion that resembles what happens when a human being experiences an emotional stimulus.

He decided to investigate further. When working with humans, police examiners like Backster watch the responses to stress under questioning. One of the most effective ways to get a response in humans is to threaten their well-being. Backster decided to try this on the plant and dipped its leaf in hot coffee. Nothing happened. So, he thought of a worse threat. He decided to burn the leaf to which the electrodes were attached. The very instant he got the picture of the flame and the action in his mind, the plant responded with a strong upward sweep.

He left the room to get some matches, and found that while he was away, the plant had responded with another upward surge. Reluctantly, he set about burning the leaf, and got a reaction, but less than before. Later Backster went through the physical motions of pretending he would burn the leaf, and got no reaction at all. The plant seemed to be able to tell the difference between real and pretended intention! These findings were confirmed by other collaborators on other species. He set up a lab and extended the study.

During one demonstration to a journalist, Backster hooked up the galvanometer to a philodendron, and then interrogated the man about his year of birth. He named seven years in succession, from 1925 to 1931, to which the reporter was instructed to answer “no” in each case. From the galvanometer chart of plant responses, Backster then selected the correct year of the reporter’s birth. That is, the philodendron detected when the “no” was a lie.

To see if the plant would show memory, he set up an experiment where six volunteers from among his police students drew a piece of paper from a hat. Five were blank, but the other told one of them to totally destroy one of two plants in the room. Each in turn entered the room. No one but the person with that piece of paper knew who was responsible for the destruction of the plant. This was followed with a kind of identity parade, in which each of the volunteers went into the room again, with the remaining plant now wired to the galvanometer. The plant showed no reaction to five of them, but the reading went wild when the “culprit” entered the room.

The plant subsequently showed a reaction to simple cellular organisms. On one occasion it reacted to Backster mixing jam with his yoghurt, which he believed to be due to the preservative in the jam killing some of the live cells. This belief was later supported by witnessing a similar reaction when boiling water was running down the waste pipe in the sink and killing bacteria.

Because Backster was interested in this reaction, he invented ways to attach his electrodes to single celled creatures such as amoeba, yeast, blood cells and sperm. All were capable of producing similar results to plants. Sperm cells, for instance, would respond to the presence of their donor. In more recent work, reported in Ervin Laszlo’s book Science and the Akashic Field,23 Backster took cheek-cell swabs from various subjects and took them several miles from their donors. In one of his tests, he showed his subject, a former navy gunner who had been present there, a television program depicting the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. When the face of a navy gunner appeared on the screen, the man’s face showed an emotional reaction — and at that precise moment, the lie detector’s needle seven and a half miles away jumped, just as it would have had it been attached to the man himself.

Some of this work has been repeated, often unsuccessfully — a point made by sceptics in the Wikipedia entry about Backster — but there is a video24 of one “mythbusting attempt” where you can see results for yourself. I do not propose to labour this area here, which I cover in much more depth in my book (chapters 5 and 6) to show the cumulative evidence that is there. Experiments which fail to replicate the results may have been poorly conducted. They are not sufficient to demonstrate that the successful ones did not happen and there is a false argument presented about lack of control subjects which irrelevantly applies human contexts to non-human investigations.

Last in this context, I would encourage interested readers to look at two books. In one, Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees,25 he describes how we have failed until recently to see the way in which forests function as entire living systems, demonstrating a combination of competition and collaboration in the ecosystem such that trees do not function individually, but rather as a collective, sharing resources and self-managing their common environment. In Entangled Life,26 Merlin Sheldrake delves into the essential part played in that story and in numerous other parts of life by mycoproteins, fungi and lichens. While this paper is focusing on the non-material connectivity in the field, the correspondence between the presence of underlying physical mechanisms for coherence as described for our human bodies and an equivalent presence within wider ecosystems shows just how much the nonmaterial and the material realities function seamlessly. It is essential that we take a holistic perspective if we are to see clearly what the I Ching describes as “The Taming Power of the Small”. A field of consciousness is fundamental, but it does not have power on its own. This is the liminal space we are exploring.

… Continue to Part 2 here.

Alan Watkins, “Being Brilliant Every Single Day”.

Candace Pert, Molecules of Emotion: Why You Feel the Way You Feel.

Mae‐Wan Ho, “Quantum Jazz, The Tao of Biology.”

Fritz Popp, “Biophotons.”

Note that photons had previously been detected by Russian biologist Alexander Gurwitsch in the 1920s, but seemingly viewed by him as causes of mutation rather than as communicators.

Hameroff and Watt, 1982; Rasmussen et al, 1990; Hameroff et al, 1992.

“Orchestrated Objective Reduction of Quantum Coherence in Brain Microtubules: The ‘Orch OR’ Model for Consciousness.”

Bruce Parry, Psychedelics, Eco-Consciousness and the Coming Crisis.

Eliot Cowan, Plant Spirit Medicine.

Alberto Villoldo, Dance of the Four Winds.

Carlos Castaneda, Separate Reality. Note that there is a dispute over whether Castaneda’s work is anthropology or fiction. Make your own decision.

Michael Harner, The Way of the Shaman

Malidoma Patrice Some, Of Water and the Spirit: Ritual, Magic, and Initiation in the Life of an African Shaman

Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy.

Dorothy Maclean, To Hear the Angels Sing.

Machaelle Small Wright, Perelandra Garden Workbook: Gardening with Nature Intelligences.

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees.