Featuring:

– Understanding collective intelligence

– Lemmings are not stupid

– Meeting people where they are

– Don’t oversimplify developmental perspectives

There is some Spiral Dynamics in this article, but it doesn’t matter if you are not familiar with it.

Something that Clare W. Graves didn’t say: “People have a right to be who they are, as long as they are not less conscious than I am.”

Something that the development of consciousness doesn’t assume: There is a continuous and sustained upward movement.

It is all too easy for us to focus on individuals like Trump, Musk and Bezos. This distracts us from the more difficult task of genuinely understanding why half of America believes in their solution. It also encourages us to treat that half of the population, and their equivalents across the world who support similar regimes, as stupid and gullible. What if doing that causes us to miss seeing what is really happening?

Developmental perspectives of all kinds present us with models in which the later values systems are implicitly more advanced than the earlier ones. One can easily read Maslow’s pyramid as implying that self-actualising man is somehow superior to those who are “merely” able to meet their physiological needs or find love and belonging. Granted, it is natural for us to be aspirational, and we probably read the diagram from a perspective where we ourselves are already at the self-esteem level, but Maslow’s pyramid has a wide base that conveys stability. In addition, the model was constructed in a less volatile era where progression seemed reliable overall.

Maslow’s model also leads towards a view that humans are responding to actual conditions. While that is true, it lacks the nuances which are required to explain the growth of populism. The majority in the West do not risk physiological needs, nor are they truly insecure. Yet even countries like Germany and Britain, with well-developed health and social care systems, are experiencing that political pressure.

I want to invite us to explore a perspective which assumes that all people are expressing the intelligence of the system. This may go against the grain for progressives who see what is happening as a failure of education, a result of media manipulation or gullibility in the face of lies. It is not that I am questioning those aspects of reality, but rather that I am asking why manipulations are successful and suggesting that the cause is not in the actual conditions of existence but in the perception of them. Progressives can provide any number of rational reasons why people are wrong, and why they would choose differently if only they understood. That thinking loses elections.

Rational is not the same as intelligent. Consciousness includes lower levels of awareness as well as higher ones. Developmentally, humans feel before they think. We pattern-sense before we analyse. There is an old and often-ignored truism that the intelligent person is one who can rationalise their prejudices. That pattern-sensing, feeling and intuiting is not wrong; it is part of what the collective knows and whether we like it or not, is a reality that we must see for what it is and respond to as best we can. And if, as my title suggests, the system is breaking, we should prepare appropriately.

There is a mythology about lemmings, created by a Disney film, that they stupidly commit mass suicide. While the story is not true, there is a truth inside, which is that lemmings migrate en masse when food is scarce and the scarcity can be a result of typical rodent breeding patterns. They won’t jump off cliffs, but they will try to swim across large bodies of water and they “accept” the losses involved. The point is that they are collectively doing the best they can to survive in difficult conditions. It is the most intelligent response available to them. Lemmings, or at least their genes, are not stupid.

And neither are humans. What we are seeing politically can be summed up as “it’s the system, stupid.” I want to talk about the leaning tower and why the system is breaking. The tower survives because of massive engineering to shore up its foundations and prevent its collapse, but don’t be misled; you can’t live in it (though you can visit the inside, maximum 30 people at a time).

So I want to talk about another developmental perspective – that of Spiral Dynamics. If you don’t know the Spiral and some of what follows about colours and stages doesn’t have meaning for you, it doesn’t matter. Most of the dynamic tensions described speak for themselves, so I encourage you to follow what you can through to the conclusions.

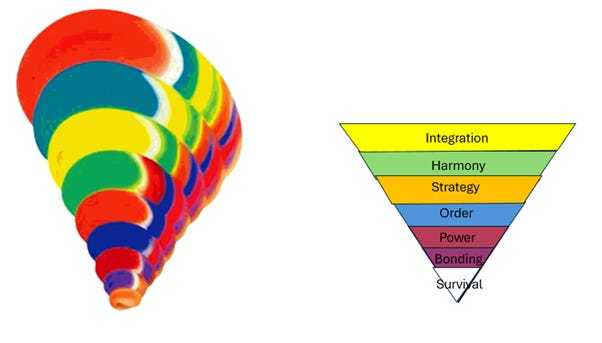

The most common graphic for the Spiral looks like this. It is the opposite of the Maslow perspective in that its narrow base represents the low bandwidth of awareness available to those in survival levels, whereas its wider and thicker bands depict the increasing complexity of later systems and a more modern world. Depicting it like that it might make us think that it can balance on its point or, at least like a child’s spinning top, stay upright against the pull of gravity. It doesn’t show what can go wrong and it is blinding us to what is already going wrong.

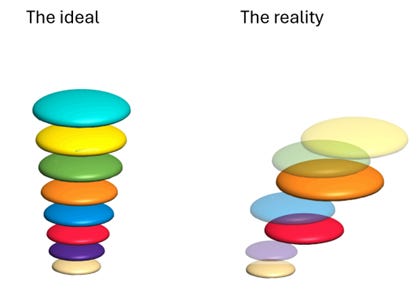

While the Spiral is a model of human socio-psychology, not a piece of engineering, it does depict the nature of societal structures, and structures do benefit from an engineering perspective. The core model above is an idealisation of development. It is not a depiction of reality. For example, it doesn’t represent actual numbers in the current population. If it did, there would be more Red and Blue, and less Orange and Green. Nor does it depict whether the stages are functioning in a healthy way. They are not, as we will see. And in regard to the relationship between the stages it implies that the systems are capable of sustaining the ones above. That is also not the case, ideal but not real. We are blind to what is going wrong partly because we have a kind of faith in the developmental trajectory, and this causes us to oversimplify the dynamics that cause regression or collapse.

There are myriad reasons why people and systems alike are under stress, and I will list just a few of the dynamic tensions in today’s reality.

The Green system has generated much confusion. While its core values are human bonding, caring and harmony, what it has manifested has often been divisive. Supporting individual difference is not always in balance with care for the collective, such that “wokism” can be hostile and excluding. The Gravesian principle that people have a right to be who they are does not extend to those who disagree.

The Orange system, based in thinking and structures that treat humans as being able and entitled to control and exploit the world, has created effects such as environmental damage, climate instability and ecological breakdown. Large numbers of people experience these as base-level threats, increasingly so as economic pressures like the costs of rectification kick in. Psychologically they become survival issues.

The Orange system has for decades encouraged high geographical mobility, scattering families, fragmenting Purple quasi-tribal bonds and organised Blue social collectives. People may not even know their neighbours, are unable to care for their grandparents or mentally and physically challenged members of their communities as they once would have. In many countries such support has been outsourced to professionals in Green state-run social systems. This conflicts politically with the desire for lower taxation, placing the resources required beyond what can be sustained. Voters often don’t see the connection; they want their money without dropping levels of care. In healthcare this is compounded by ageing demographics and medical systems which preserve existence but not quality of life. In the US, 250,000 deaths per year are attributed to iatrogenic causes.

The standard Blue-Orange response to our economic challenges is that “growth” is the solution. This is incompatible with the need to reduce energy and limit resource usage. Even renewable electricity generates heat; we are not close to circular production methods; expectations are still being created politically which are not deliverable. Masses of people are in the denial phase of the grieving cycle, with blame and anger being close behind.

The systems of order which arose in Blue should in theory provide structural cohesion. However, those systems were too rigid to support the growth of Orange strategy and economic success. Indeed, that feeling of restriction is why the Orange system emerged. Being seen as anti-growth and as disincentivising entrepreneurial activity caused many of the ordering systems to be dismantled or weakened. Those that remain are too clumsy, slow and under-resourced to constrain the speed of movement by aggressive corporations and financial manipulators, plus Orange can afford better lawyers. That centre is broken and cannot hold.

When conditions are turbulent there is a desire for strong and clear leadership. However, Red abuse of power is not seen clearly. Green progressives are often hostile to the expression or use of power even when that power is healthy, essential to the provision of clarity and is urgently desired by those who are fearful. The result is that strong leadership is only available from the sociopathic. Voters are willing to overlook their faults, tolerate the lies and ignore their self-interest. At the same time, they see progressive voices as failing to meet their concerns, weak or unwilling to face tough choices.

The Purple system would in theory provide bonding mechanisms to healthy nations and cities. However, when under pressure it is easily exploited to create division. America is far from unique in that respect, though the divide and animosity are particularly stark there, more now than ever. So the base of the inverted pyramid has very little strength, making the foundations too weak to support any weight from above.

I will limit this list to one more item, which covers several stages. Support of Western societies and cities requires infrastructure. In the UK, the consequences of living on a legacy which we have failed to maintain shows up in roads with potholes that do not get filled (the cost of this estimated as £0.5 billion annually in damage to vehicles) and water and sewerage systems that cannot cope with demand, so that untreated sewage has been discharged into rivers and seas. We have not built enough houses to accommodate a growing population, cannot police law-breaking slum landlords or cope with rising costs to citizens from the supply-and-demand pressures.

In the above I have tried to illustrate that the Spiral (or any other developmental system) must not be viewed in a simplistic and over-optimistic way as indicating a steady upward movement. We might be lulled into a false sense of security by a historical reality that seemingly got us to where we are despite the challenges. Thus far, we have solved problems faster we created them; looking backwards smooths out the bumps with rose-tinted hindsight and discounts the price that was paid. Granted, there are more humans alive than ever and larger numbers of us live at a higher standard than ever. Regardless of some appalling conflicts and genocides over the years, we have avoided war on a global scale for 6 decades. But conditions now are different.

The difference is that all of the challenges in the list exist alongside the others and cannot be separated from one another; rather, they compound one another. The problems are systemic and while people may not intellectually understand them in their full complexity and interrelatedness, they are not stupid; they sense and feel them, and that is scary. Rather than imagining that they can and should make the sensible choices that intellectuals and pundits would ask of them, we need to truly meet them where they are in an acceptance that they and their anxieties, too, are a component of a living systems intelligence. Rather than pretending that our progressive solutions are capable of meeting this metacrisis,1 we must acknowledge that not only are they less stupid than we present them as being, but also that we ourselves are less intelligent than we like to think. I don’t have the solutions, and I don’t believe that you or anyone else does. I can see useful components of future improvements, but I can’t see how we put them together when faced with political and economic structures which are too monolithic and entrenched to facilitate the changes that are needed. Those structures are terminally dysfunctional and beyond changing. The thinking that created them is still dominant.

This is why I started from the viewpoint that the system has to break. Only the collapse of those monolithic pillars of existence will create the freedom for something new. And that is where our focus needs to go, because we must be as ready as possible to deal with the fallout, and as nimble as possible in creating the essential islands of coherence2 that will regenerate society from the bottom up when the chaos is at its most intense.

One of the pillars is not only structural but also based on a mindset which encourages the belief that there can be someone, or a group of people, who can lead us out of this. I don’t believe that is possible, or not in any form that we would recognise. One flaw here is the implicit belief that these are problems with solutions, when what we face is a predicament. Driving a top-down solution would almost certainly attempt to re-apply the ways of thinking that created the problem, and it would most likely be usurped or exploited by the latest in the long line of those who merely want power. In any event it would not engage with the predicament, its unsolvable character and our need to adapt to the reality with different responses.

So there is the irony. We have elected power-hungry sociopaths to lead us – or where they have not (yet) been elected, they continue to operate destructively inside the system, creating division and dissent.3 The desire for such leaders arises from fear and some of that fear has its roots in the belief that we are powerless and voiceless. The system must break because it is not capable of sustaining itself; arguably not even worthy to do so. Therefore it needs to be replaced by something new, built from the bottom up with the engagement of an empowered populus which is learning to adapt. In case anyone might read this as an encouragement to communism, it is categorically not that. Communism was never a bottom-up system. Whatever we build now will not be anything that we have seen before and probably not capable of being called an “ism”. It will have to be organic, a living system, an ecology, because the only systems that have sustained for millennia are not intellectual constructs. They are rainforests, coral atolls and savannahs. These co-evolved and were autopoietic. They are not “in balance with nature”, they ARE nature, and we will need to emulate that with all the sensitivity and humility that we can bring to the task. We will need to be a part of the process, no longer attempting to control it.

Much as the breakdown looks likely to be painful, I welcome it. It is a source of transformation. I hope to survive it and wish that for others, but my survival is not important. Maybe from the perspective of the planet or the galaxy human survival isn’t either, but we are quite an extraordinary species, souls as well as bodies, and we have created much that is special and wonderful. I write this with Bach violin concertos playing in the background. They have been around for a few hundred years, and I suggest they, like so much of human culture, are worthy of a few hundred more. Meanwhile, we would build a world for our children and grandchildren.

Blaming appalling leaders and those who elect them won’t achieve that. It distracts us from the awareness and becomes an excuse to ignore this reality; the transformation is something to work for and it is our task to do.

Also a polycrisis, but the polycrisis is at the current level of complexity whereas the metacrisis is arising from the next level.

Ilya Prigogine – “When a complex system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to shift the entire system to a higher order.”

Farage, Le Pen, AfD, Wilders, etc., etc.

Thank you for an amazing article, I have felt what you write for a long time, after 20 years of study I am able to rationaly understandit but am far from being able to elucidade where we're at as clearly as you have in this piece!

The only thing I would add is to suggest it's important to add the lens of the "Meaning Crisis" as developed by John Verveake to the analysis. The meta-crisis being a symptom of humanity's meaning crisis.

Much appreciate your perspective.

One thing got me thinking: one system that DID survive for two millennia is Christianity/ the Catholic church. I'm surely not a fan, and from my limited perspective I don't see many healthy elements-but I'm wondering what can be learned from them regarding stability